MightyGanesha.com

Kiddos,

this next review is going to have me all navel-gazing and philosophical

so prepare to put your deep hats on … What is the making of a man? If

someone were able to peer inside the brain of the average Joe and pull

apart the emotions, moments and events that made him what he was, what

would they show? How would they show it? Apply this query to the

kaleidoscopic existence of one Robert Allen Zimmerman, better known to

the world as Bob Dylan, Premier Laureate of American Lyric, and the task

of recording and presenting someone’s life becomes nearly

inconceivable.

Kiddos,

this next review is going to have me all navel-gazing and philosophical

so prepare to put your deep hats on … What is the making of a man? If

someone were able to peer inside the brain of the average Joe and pull

apart the emotions, moments and events that made him what he was, what

would they show? How would they show it? Apply this query to the

kaleidoscopic existence of one Robert Allen Zimmerman, better known to

the world as Bob Dylan, Premier Laureate of American Lyric, and the task

of recording and presenting someone’s life becomes nearly

inconceivable.

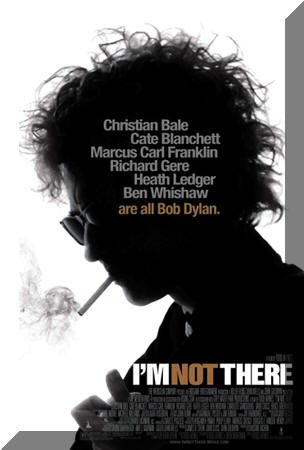

Todd Haynes has given us a brave, trippy, and wholly original biopic. The much discussed talking point of this film has been the casting of six actors in the role of Dylan. However, this isn’t completely accurate, as at no point is Dylan’s name ever spoken. Trading back and forth between colour and black and white, the gist of the piece is that each of the pseudonymed (- and anonymed) characters either represents a specific period of Dylan’s life, or otherwise enacts tableaus of influences that created the songwriter and his art. Confused? Babies, I’ve just gotten started… I’m Not There portrays actual events in Dylan’s life only coincidentally, yearning alternately to have the audience feel his experiences through metaphoric vignettes that may or may not have ever had anything to do with Dylan. The audience has to play a game of connect the dots in order to figure out the portrait of Dylan that Haynes has painted: The further result of that exercise being an audience unsure if they’ve found out something or nothing about the subject of the story, which is, most likely, totally intentional (- FYI: Bob Dylan gave his approval for I’m Not There to be made).

Precious little could get me to say negative things about the man who brought the world Velvet Goldmine (- and JRM!), and I hesitate to begin here. I can appreciate Haynes’ creativity and ambition that brought about this fascinating premise; I just think something got lost in the translation from groovy, innovative concept to filmable narrative. The Alice Through the Looking Glass effect via the lack of straight, linear narrative is intentional, and it’s a really neat gimmick for a while, but as the film wore on, so did my nerves. The first “Dylan” you meet after a rapid-fire introductory montage of Zimmermans is Marcus Carl Franklin, an African-American boy dressed as a depression-era hobo jumping into boxcars with a guitar case emblazoned with the words, “This Machine Kills Fascists”. He calls himself Woody Guthrie and amiably discusses his philosophies with anyone who asks him. His words could easily come from the mouth of a Mississippi-born bluesman, but Woody has his first creative epiphany when a wise hostess sees through his pose and advises him to sing “about his own time”. This sets us off to meet the other “Dylans” – the revolutionary folkie, the spoiled, despised “sell-out” who commits the crime of plugging in an amplifier, the ambitious actor and unfaithful family man, the hermit, remote and out of time, and the raw, purist poet, still angry after all these years.

Haynes gets great performances out of his cast. Notable not only because of the stunt-factor, Cate Blanchett as the Dylan of the mid-1960’s, is remarkable. Her introduction is the best scene of the film: Stepping out onto a stage at an outdoor folk festival, Dylan and his band pull out uzis out of their guitar cases and obliterate an unsuspecting audience. It’s a great metaphor for the madness that followed Dylan after he had the temerity to play an electric set, veering away from his worshipped, acoustic roots. His very humanity is questioned because of the act, and shouts of “Judas” greet him in concert halls. It’s not all bad news as Dylan is still seen as a pop maharaja; with society matrons, serious journalists, well-heeled groupies, and a quartet of romping moptops all vying for a spot at his feet, even as he serrates them an intoxicated, acid tongue. Blanchett’s slim feminine frame (- and indeed her French manicure) captures a mutable sexuality and a blithe, pixie-like charm. One understands the moth-to-the-flame magnetism of Blanchett’s version of Dylan. (- Warning! Tangent ahead: While I adored the casting of Blanchett as Dylan, I saw a nuanced, feral rawness, and strength in her performance that I more closely associated with another rock god and I wished someone would think of casting her as John Lennon. I wonder if Blanchett would consider playing another male pop icon?) Christian Bale is momentarily brilliant as two shades of Dylan, the Village folkie and unwilling face of a generation (- Julianne Moore makes an even more minuscule appearance as a Joan Baez-esque muse); and later Bale is the born-again Dylan, infusing his hymns with the same zeal that moved him in the early days. Of all the portrayals, Bale’s was one of the shortest and that’s a mistake. His and Blanchett’s segments are the most seamless of the lot and when they were off screen, I found myself waiting for Haynes to bring them back. (- Ben Whishaw as the primal Dylan, young, brutal, clear-eyed and wise, could’ve also stood a few more seconds.). Heath Ledger’s scenes as the shallow actor and disloyal husband Dylan go on forever and never click despite the presence of the luminous Charlotte Gainsbourg as his forgiving wife. Richard Gere’s segments as the earthy, scruffy outlaw hermit are the most oblique and so vague in narrative as to be tedious.

There are rousing musical sequences where the audience is allowed to revel in the joy of Dylan’s songcraft all too briefly intercut throughout the film; Richie Havens jams with Marcus Carl Franklin on Tombstone Blues, a moving brass band version of Goin’ to Acapulco sung as a funeral dirge by Jim James and Caleixco, and John Doe raising a gospel choir to Pressing On (- with Bale lip-syncing). Had the film been a collection of Haynes-directed music videos, I would have been one happy pachyderm.

I’m willing to concede my passing knowledge of the finer details of Dylan’s life, with a few exceptions - I’m more intrigued by his songs interpreted by other people than the man himself - but I came in to I’m Not There completely willing to learn. This is no film for Dylan novices. Many notes in the film speak to moments in the life of Dylan that fans much more fervent than me would understand, and with my topical awareness of the subject and the purposeful psychedelic structure of the screenplay, I felt lost. But for those strong performances by a cast I liked and my appreciation of the ingenuity - if not the execution - of this original premise, there was almost nothing that enables the film to rise above the confusion of the overall proceedings.

My feeling is had Haynes chosen to make two films; one a (- relatively) direct portrayal featuring the folkie, the 60’s pop icon and the born-again spiritualist, then a second painting the more impressionist, visceral portrait using the segments of the little boxcar boy, the actor, and the outlaw (- Ben Whishaw’s character could have fit here or there); either would have made for a more solid film than the aggressively arty, undercooked jumble of both worlds that doesn’t fully satisfy.

~ Mighty Ganesha

Nov. 12, 2007

© 2006-2022 The Diva Review.com

Photos

(Courtesy of The Weinstein Company)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|