|

In

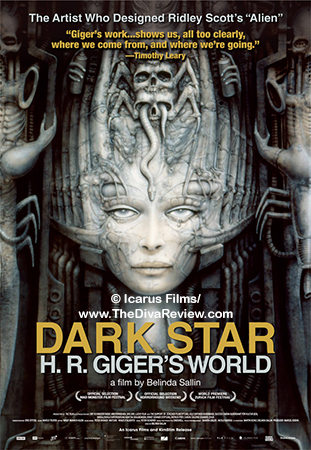

1979, a sleeper hit movie by a little-known British director revitalised

the genres of science fiction and horror. A story of (wo)man

versus both monster and machine, Ridley Scottís Alien was an unexpected

blockbuster that plunged its audience into a dark future world, both

grim and strangely lush. We boarded a derelict spaceship full of

otherworldly technology, interiors that resembled metal vertebrae, and

dead giant space travelers surrounded by pulsating eggs. Galaxies away

from the basic Area 51 bug-eyed extraterrestrial; Alienís titular

creature was a nightmare of skeletal animal and human physiognomy

blended with cool, sleek, unearthly attributes that triggered a primal

fear in anyone who saw it. For many, this was their introduction to the

surreal, shocking and beautiful world of artist H.R. Giger. In

1979, a sleeper hit movie by a little-known British director revitalised

the genres of science fiction and horror. A story of (wo)man

versus both monster and machine, Ridley Scottís Alien was an unexpected

blockbuster that plunged its audience into a dark future world, both

grim and strangely lush. We boarded a derelict spaceship full of

otherworldly technology, interiors that resembled metal vertebrae, and

dead giant space travelers surrounded by pulsating eggs. Galaxies away

from the basic Area 51 bug-eyed extraterrestrial; Alienís titular

creature was a nightmare of skeletal animal and human physiognomy

blended with cool, sleek, unearthly attributes that triggered a primal

fear in anyone who saw it. For many, this was their introduction to the

surreal, shocking and beautiful world of artist H.R. Giger.

Despite his acclaim after creating Alienís designs, the Swiss-born Giger

was neither a neophyte nor an overnight success. He had worked on

paintings, sculptures and other mediums, selling posters and being

commissioned for record covers (Notably 1973ís Brain Salad Surgery by

Emerson, Lake and Palmer) and magazine work since the mid-1960s.

His bold embrace of science, sexuality, flesh and metal in a style he

dubbed, ďbiomechanical,Ē gave expression to dark facets of human nature

while celebrating life and humanity. Known mostly in Europe and

Scandinavia, it was the release of his 1977 book, Necronomicon, his

pieces in international science fiction publications, and of course the

creation of the world of Alien that skyrocketed him to art world

royalty. Despite the endless interpretation and popularity of his work,

and his amazing output of books, prints and sculptures even into his

seventies; there has been precious little biographical information about

the artist, who routinely chose to let his work speak for him. Dark

Star, completed days before the artistís tragic passing after a fall in

2014, seemed to be the best chance the public might ever have of knowing

what exactly were the demons and angels that drove H.R. Giger?

Sadly,

even after viewing the documentary, I still have very little idea.

There

seems to be a fearfulness infused in Director Belinda Sallinís narrative

that forbids her from asking a single question of any value. Was she

afraid to insult or lose access? Her failure to make pertinent

inquiries of Giger about even the simplest matters of interest; his

process, his worldview that inspired his creation, his rabid fan

following, the publicís perception of his work, his reaction to the fame

heís achieved, made me throw my hands up in disgust. Whatís worse is

that Giger himself in those precious few moments when he does talk about

something important to his life, like the suicide of his troubled early

muse, Li Tobler, seems perfectly congenial and willing to open up and

discuss anything. We are shown a lot of footage of his many helpers and

associates, like his adoring wife, Carmen, who is one of the few to give

us viewpoints at all about the context or meaning of Gigerís pieces, yet

thereís very little follow-through. Like Gigerís omnipresent

mother-in-law discussing their correspondence with Twentieth Century

Fox, the company that produced Alien, in what weíre led to believe is a

tricky or possibly contentious business relationship, but weíll never

know why the lady sighs so deeply when reading their letters.

Infuriating is bringing in Gigerís archivist and his display of

something as rare as one of Gigerís earliest sketches that is on camera

for less than the blink of an eye. The archivist also brings up a

subject that I was curious about, but is only mentioned in this moment

when the gentleman refers to Giger having grown up during World War II

and therefore bearing an instinct to collect everything. I understand

he lived in neutral Switzerland, but is it naÔve to think itís possible

people in that region felt some effect of the war or its aftermath? We

are shown early pieces of soldiers in gas masks with no further

elucidation.

There

are so many missed opportunities to delve deeper into questions and

situations that are specifically posed for the camera, itís

mind-boggling. We see Giger standing in a room he calls the ďSpell

Room,Ē it is bedecked in satanic imagery; upside-down pentacles,

Baphomet, etc., and so many interview subjects discuss the ďdarknessĒ

that Gigerís art seems to have a connection to, yet never is the man

himself asked to give his views on that common association. Also, there

is the problem of Sallin jumping from one place to another: I am not

sure where that Spell Room is? Are we in Gigerís sprawling, maze-like

home (If so, it appeared to be the only place not covered in dust,

which might account for his saying it was his favourite)? Are we in

the Giger museum? Are we in his famous bar? Are we at his gallery

show? The locations change without notice so much, I gave up trying to

figure it out; another regret for anyone who would have enjoyed seeing

these Giger-drenched spaces.

There

are incredible indulgences that make no sense, like filming dinner party

after dinner party with the same group of people time and again. Sallin

interviews Gigerís assistant, a fifty-year-old, eternally chapeau-ed

death metal musician named Tom Gabriel Fischer, and he talks about

Gigerís influence on him and his music; which means we are forced to sit

through one of his groupís songs. She spend more time on Fischer than

she spends on all of Gigerís childhood. It would have been nice to know

what was the spark that encouraged Giger to begin drawing? Who in his

school years encouraged him? In this story, he is a small child whose

father brings home a skull (Why? How?), and was scared of a mummy

in a museum once, and then as an adult, shows up at a poster printerís

shop to start mass producing his pieces. Voilŗ.

Other

things conspicuous by their absence was the huge effect that the

pioneering sci-fi magazine, Omni had on Gigerís international career, by

placing him on their covers in the days before Alienís release. Sallinís

focus is very local, which restricts this view. Watching Giger so

calmly received by an audience at a gallery show in Linz and how very

sedate they were, made me wonder what kind of reception he would have

had from his US fans? Yes, there are the requisite tattoo displays, but

the only time we see someone truly affected by meeting him is one

gentleman, who, despite firmly placed sunglasses is stoically trying

Ėand failing adorably - to hold back tears at meeting his idol. SallinĎs

purview feels very limited.

In

abundance are old film clips of younger Giger moodily walking around (As

all young artists naturally do), unnecessary shots of his poster

printerís sexy hot pink platform boots, and other pretentious period

offal. While the clips are fun at first, it would have been more

interesting to see more of Gigerís photography which influenced his

paintings and sculpture (Somehow, Sallin never asks how other mediums

moved him). In the recent film footage, we see a fragile man in

poor health, moving slowly, mostly with help, and judging by the

sideways movement of his mouth when speaking, he seems to have been

affected by a stroke (another thing weíll not find out). Yet, he

is in very good humour about his life. For someone who created such

nightmarish visions of death, the hereafter and the future, it is

interesting to hear him say he does not care for an afterlife; that

death is the end and having done all he wished to do, and seen

everything he wanted to see, was satisfied. More insight like that

wouldíve saved this film.

What

does provide a small, desperately needed bit of charm (as Sallin only

allows glimpses of what appears to be Gigerís impish personality to

shine through) are moments like his interactions with his beloved

cat, Muggi. Muggi is really the star of the show, cavorting here and

there, demanding to be carried by interview subjects, completely doted

on by his owner. Muggi is such a spoiled kitty that when we are taken

on a ride on the railroad Giger built inside his house, Muggi saunters

across the tracks as Giger shouts for him to get out of the way before

slowing down to allow the feline to calmly stroll off. In the war

between cat and machine, in Gigerís house, the cat wins.

Sallinís access to the personal, daily life of Giger is the most

remarkable thing about the film Ė wasted though it may be. If you ever

wanted to know what itís like to live in the home of the greatest

cyberpunk artist, this movie is for you. That said, just because a

filmmaker is granted access to a subject, doesnít mean they should

tiptoe carefully around them and get no narrative of value. Pretty

pictures and candid shots of the master at rest werenít enough; I felt

as if Iíd hardly learnt anything new about this fascinating figure in

art and cinema history. Sadly, with his death last year, this is

probably the best look at the man and artist weíll ever get, and for the

opportunity lost, that is a real shame.

As a

nearly lifelong Giger fan, I was terribly excited for the chance to

discover more about this artist who changed so many mediums and whose

designs meshing the worlds of nature, mechanics, the occult and humanity

will continue to influence other artists for generations to come. What

made him tick? How did he view his own work? Unfortunately, Dark Star

falls far short of asking those questions and so many more. I wondered

if Dark Star was taking a naturalistic angle and just following Giger

around being Giger? Unfortunately itís too contrived and posed for

that, so the result just feels hollow and lazy. If Director Sallin was

going for a hands-off, fly-on-the-wall approach, she fails utterly, and

it feels like an opportunity tragically wasted. This true artistic

pioneer is an enigma that this documentary seems determined to remain an

enigma.

~ The

Lady Miz Diva

May 15th,

2015

© 2006-2022 The Diva Review.com

|