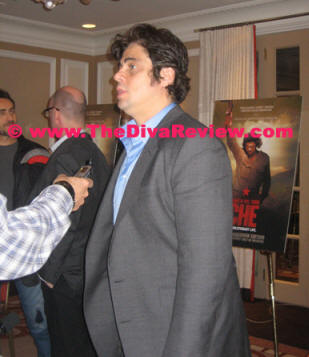

Hey babies, Viva La Revoluciůn as Benicio Del Toro, DemiŠn Bichir and Director Steven Soderbergh sit down to parlay about t-shirts, breakfast with Fidel, the death penalty and their roles in the controversial biopic, Che.

Power to the People!

Q:

Itís taken a long time and a lot of struggle to bring Che to the silver

screen. How are you feeling now that itís done?

Q:

Itís taken a long time and a lot of struggle to bring Che to the silver

screen. How are you feeling now that itís done?

Steven Soderbergh: This has taken longer than anything else that Iíve been involved with. Although The Informant, which weíre in post with right now took six years, but it wasnít anything like this. It helps mitigate the negative responses when you know what it took to just do it at the end of the day. And the film is hopefully going to function as a provocation, so when all this stuff was going on at Cannes and you get emails form your friends saying, ďOh, Iím so sorry about the review,Ē whatever. Our attitude was to go there and suck up as much of the oxygen of that festival as we could and to detonate and thatís what happened. I mean, pro or con, we wanted to make a big noise and so I came away pretty satisfied with the way that went.

You know, it used to be in American cinema culture, in that great era of Ď66 to í76, it used to be a good thing that you made thing that polarized people. That was like a badge of honour. And those kind of movies would still be talked about at the end of the year, or might even show up on a list for an awards show, not anymore. The consensus is if you donít make something that receives pretty universal acclaim that the movieís a failure, or thereís something wrong with it and it gets pushed off to the side.

Q:

Benicio, what has it been like for you to devote such time and effort

to this role?

Q:

Benicio, what has it been like for you to devote such time and effort

to this role?

Benicio Del Toro: Definitely, itís the longest one of my career and the hardest one.

Q: Do you think there is anything worth starting a revolution about today?

BDT:

Iíd say youíd do it by voting. I think thatís what weíve seen now.

Respect the voters. A good example is Obama being elected president of

United States and another example would be an indigenous president

elected by the people of Bolivia. I donít think that was even in Cheís

radar back in 1964, I donít think it was in anyoneís radar that an

African-American could be elected by the people of the United States or

an indigenous president could be elected by the people. So Iíd say

having an election is the way to do it.

BDT:

Iíd say youíd do it by voting. I think thatís what weíve seen now.

Respect the voters. A good example is Obama being elected president of

United States and another example would be an indigenous president

elected by the people of Bolivia. I donít think that was even in Cheís

radar back in 1964, I donít think it was in anyoneís radar that an

African-American could be elected by the people of the United States or

an indigenous president could be elected by the people. So Iíd say

having an election is the way to do it.

Q: Che Guevara and Fidel Castro were both men of strong passions. Which passions of his did you relate to most closely?

BDT:

I relate with a lot of the morals, education, medicine. I relate

with some of the things that he fought for. I donít relate with

the death penalty, but then again, Iím an actor.

BDT:

I relate with a lot of the morals, education, medicine. I relate

with some of the things that he fought for. I donít relate with

the death penalty, but then again, Iím an actor.

DemiŠn Bichir: I guess I relate to El Jefe in many, many ways. You need a revolution when things are not equal to everyone, right? And in Mexico, we had a revolution a hundred years ago and it seems like we need another one. Nothing has really changed. And if the vote was respected everywhere, then you have that type of revolution. Iím talking about Mexico and some other countries. So hopefully we won events here, but it seems like in places like in Mexico itís not really respected, the vote. Then there is no other way, right? But I think the last armed revolution that we saw was the one that these guys did in Cuba. I think in Mexico we need a cultural revolution more than anything else, so people can really learn to read and that way get educated and defend themselves better.

The

Lady Miz Diva: Benicio and DemiŠn, can you tell me the research

you guys did with the people who knew Che and Fidel and how that

affected your roles?

The

Lady Miz Diva: Benicio and DemiŠn, can you tell me the research

you guys did with the people who knew Che and Fidel and how that

affected your roles?

BDT: I got a chance to speak to his brother in Argentina, his younger brother. He did two trips through Latin America; the Motorcycle Diaries and the second one where he goes and he never comes back and he ended up in Cuba. I talked to the guy that went with him all the way up to Bolivia his name is "Calica" Ferrer. Then after that, we met with his 2nd wife Aleida, his daughter, his son, his 2nd daughter. We met with the survivors of Bolivia, the three guys that were with him the last day in El Yuro ravine where he was captured. There are three survivors that are still alive, one lives in France and the other two live in Cuba and we met with all three we met with guys that were with him during the Cuban Revolution.

It influenced the performance quite a bit, because you get to talk to someone who actually was with him. Little things from how did they deal with him when he had asthma? The bottom line is what I got from them right off the bat is that respect. Then there was this love, and then at the end they made sure to know that he was made out of flesh and bones. That he was not just some superhero. There were so many little things I took from all of them in some ways.

DB: I wanted to meet Fidel and thatís obviously impossible. I think it was impossible then {during the Revolution}, too. But a character like this, so well known by everyone, there are so many things about him in books and pictures and video and footage, so I had the chance to get access to all that, so that was my material, the things I worked with. Lucky enough I had five months to prepare, so I had Fidel for breakfast, lunch and dinner for five months.

Q: Was there anything rewarding about playing the role of Che?

BDT: There were many things that were rewarding. The most rewarding thing is the people around you that were involved in this movie, it was a motivator. The actors, the set designer, the director of photography and the director that was really a motivator when youíre in doubt and you see people just doing it, you suck it up and you push for the best you could do. And seeing other actors, from DemiŠn to actors that came in that were stars in Spain {who} came in to do just a cameo, and came in focused and you see that dedication to it, thatís a big motivator, too. A rewarding thing that you feel that I canít complain here, I canít just lick my wounds over here, I just gotta keep going.

Q:

What do you think people will take away from watching Che? What did you

take away?

Q:

What do you think people will take away from watching Che? What did you

take away?

SS: Itís certainly not meant to be a recruitment film. All I would hope is that somebody comes out of the movie going, ďIs there anything I feel that strongly about?Ē ďIs there anything in my life I feel that passionately about that I would engage at that level?Ē thatís really it.

We were talking about motivation; I felt so lucky to talk to people who actually were with him was pretty intense. To be that close to history thatís that significant, is really something. To Dr. Fernandez Mell, whoís in the movie as a doctor in the last part near Santa Clara, and who was one of the people who was close to Che, said the great thing, he said, ďYou had to love Che for free.Ē That really stuck in my head and itís been interesting in talking about the movie to have people say, ďOh itís kind of glorification of him and obviously, itís very pro-Che,Ē and yet fifty percent of the movie claim that itís cold. And what I got from all the people that I talked to {That knew him} is that there was a certain distance in him thatís partially, I think, in his personality, partially a result of being transposed into another culture although itís still a Spanish-speaking culture, itís very different than the one he grew up around and part of it is the obligations and responsibilities of being a leader. That phrase always stuck in my head, and unless he was in doctor mode that heís apart from people. Thatís the impression I got.

BDT: I think movies like this are good to present. Thereís many other stories that can be told, not only about Che Guevara, but about other people who sacrificed their life for a cause that you might say is just. So, Iíd like to see more movies that are in this vein, or at least the effort. I like the effort.

At some point, I was in Stevenís office here in New York and I think he saw the fear on my face. This fear of like, ĎWell, here I am. Who do I think I am playing Che Guevara? Here we are doing this movie about Che Guevara thatís not only a movie about Che Guevara; itís a movie about the history of a whole country.Ē He said something to me, ďItís impossible to do a movie about Che. Itís impossible to play him. Letís try,Ē and that to me, was very much in the way I look at life, you just try and you give it your all and hope for the best. I think if you stay true to yourself, thereís a light at the end of the tunnel.

SS: Well, yeah, the alternative is giving up and that seems worse. Even making something that people hate, to not take one of the hundreds of opportunities we had to just let this thing fall apart. There were so many times when literally by just not picking up the phone or answering an email, I could have let the movie crater. To just make the choice to pick up the phone, write the check, do whatever you gotta do, keep this thing going. Getting to the end of it was all we needed out of this, frankly, because there were just so many times where you thought it wasnít gonna happen, or you had friends say, ďItís not gonna happen. Why are you investing yourself when itís not gonna happen. Youíre not gonna get the money.Ē But then thereís this vague feeling when you get out of it of Ďwas it enough' in the larger sense, was it enough?í

Weíre seeing the results now of a system in which money is being made that doesnít represent anything. It doesnít represent any labour, or product, or idea. It's meaningless, and that canít sustain, it canít hold. This is what happens. So you canít come out of this having spent eight years on it and watch whatís going on and not start thinking about that. What does a dollar represent? Does it represent anything and if it doesnít where are we going? I think for all of us, thereís a bomb residue that stays with you. If youíre paying attention, it has to.

DB: I donít remember encountering a character that made me feel so guilty and so lazy. Because no matter how hard I work, they always worked double and triple and once thing that Fidel always said up until now - I mean, as we speak heís writing, he writes every day. He writes a column about his thoughts about the world and he reads a lot Ė he always said it was a waste of time even shaving. Thatís why he keeps his beard. Thatís one of the reasons; he said that in his own words. In the revolution in Sierra Maestra, he said they wouldnít do that; they wouldnít cut their beard because if any intruder wanted to infiltrate the guerrillas he would have to have a six-month long beard. Also, after that he said itís a waste of time, because if you add the fifteen minutes you spend shaving your beard every day, you could use that by reading, by doing sports, so I really feel lazy, I feel useless compared to that guy.

Q:

Did you have any hesitation about making this film whether it was

portraying Fidel Castro who is still alive or the length of the film?

Q:

Did you have any hesitation about making this film whether it was

portraying Fidel Castro who is still alive or the length of the film?

SS: The inspiration really was from Benicio and {Producer} Laura Bickford cos when we were on Traffic, thatís when we started talking about it and I came along. So, you have a different angle on project when you haven't initiated it and sometimes thatís good because you can be more dispassionate about it and there definitely were cases where we had to make large, difficult creative decisions. And I felt comfortable making them because I was the Swede coming into a culture that wasnít mine and so I didnít have the sort of emotional baggage that somebody else might have, and I can say something like, ĎWeíre gonna cut everything that happened from the Granma to just before El Uvero, because we need to. Narratively, we need to do that.í Thereís a lot of great shit that happened in the first six months of the Cuban Revolution, it just had to go. Thatís easier for me cos I can stand back at it and say that needs to be amputated.

We really had the luxury of being able to do whatever we wanted to do. We had the best of both worlds; we had access to all the people that are still alive, all the material that still exists that was relevant to what we were trying to do. We had total creative control. Honestly, that mustíve been a very, very difficult or scary situation for the Cubans. I wouldnít trust an artist, frankly, but they gave us what they had.

You know what we shouldíve done; we shouldíve done the ten-hour miniseries. Thatís what we shouldíve done. Thereís so much stuff we wanted to do. The period we didnít cover which different people think means different things, the period between those two campaigns in fascinating and the Congo is fascinating. No time.

Q:

When did you decide to make it into two films?

Q:

When did you decide to make it into two films?

SS: First, we were doing Bolivia and then it started to expand. We started to think, ĎWell, you really donít understand Bolivia unless youíve seen Cuba, then he went to New York and that was cool, and we should see him meet Fidel.í It became like The Sorcererís Apprentice, it kept getting bigger and bigger and it still at that point was one large script, but it was becoming kind of unreadable, it felt like a trailer for an even longer film. I took a cue from nature, when a cell gets too big it divides to survive and thatís what needed to be done and it became a solution for the various problems we were having narratively and things became a lot simpler. It became more complicated in that the deals that we already had in place had to be renegotiated. Fortunately for us, all the people that came on to this project early were enthusiastic enough about it to redo the deal for the two films, but in the back of our minds I think we always saw it as one big thing that if you could pull it off and people could see it with an intermission, that that would be the sort of Altered States version of total immersion for four and a half hours. Thatís that the best way to get a sense of what they did, just the physical stamina required to pull this off. And as it turns out I think just in the States itís gonna be seen like there, everywhere else theyíre cutting it in half.

I needed a visual corollary to the difference in the voices between the two texts we were working from. The reminiscences of the Cuban Revolution is written after the Revolution and thereís a sort of macro hindsight at play here that results from writing about a victory, that I wanted a visual version of and that means a wider frame, a more classical approach to framing, a more traditional approach to the music. The Bolivian Diaries were contemporaneous. Thereís no perspective. Heís isolated; he doesnít know whatís going on. So visually, Iím looking at a style that makes you feel that the outcome is unclear, the outcome of a scene is not even clear. The colour palette is less inviting, the terrain is less inviting, the cutting is a little more arrhythmic, everything to give you this sense of dread. Just as youíre heading into the mountains in that jeep thereís this sense of, ĎOh boy.í And normally, you wouldnít want to do that, because youíd feel like youíre tipping the outcome, but you have the opposite problem here that usually happens in that Che has no arc, heís a straight line and so the tension is in whether he will bend. So the earlier, to me, you set up this sense of dread, the stronger he appears throughout and that was my idea.

Q:

Besides speaking with people who knew Che what were some of the things

you took away from researching him that helped you create your

performance?

Q:

Besides speaking with people who knew Che what were some of the things

you took away from researching him that helped you create your

performance?

BDT: One of the things it took to perform the character of Che, for me, is all this history of Latin America makes him. So, I went back to learn about some aspects of Latin America, Cuban history before he came into play, or Fidel came into play, and that helps you understand choices, cos otherwise, if you donít ground it in what he knewÖ I saw a list of the books he had written at twenty-one. When he was child, he was following the Spanish Civil War day by day because he had an uncle who was in Spain on the side of the Republicans. All that some into play and the choices that you make as an actor, so for me, it was more going back than going forward of what people might say now. I looked into stuff about what people might say now in retrospect. What happened with the Cuban war with Spain trying to separate; which Iím part of it as a Puerto Rican. The fight between Puerto Rico and Cuba fighting Spain to stop being colonies of Spain, then the Spanish American War, the Platt Amendment and all that stuff comes into play. Itís interesting to then look at the character like that. Maybe another thing that I did look at which was interesting for me, the last year of his life and then the very early stages of his life; he was born in a town called Rosario; at age one or two he has an asthma attack and the family just takes this child and they move to the equivalent of Poughkeepsie, New York, six hours {from Rosario} and they move there because itís dry, itís good for the child. So right off the bat, he is in this cocoon of encouragement, of love, or care, thatís really interesting to see that thatís the formative years are the mother and the father staying up with him all night long. They move to this town for the benefit of this kid. So, those are things that you look at that you start building this character. And also you have other sides too, he was daring, and he was fearless and a warrior, thatís something that he had, but there are other aspects that come into play to build this character, not just that side.

The

Lady Miz Diva: Steven, there are so many young people who wear

everything from t-shirts, to messenger bags and socks emblazoned with

the famous photo of Che Guevaraís face on it without having a clue who

he was and what he did. What do you think those young people are going

to take away from seeing your film?

The

Lady Miz Diva: Steven, there are so many young people who wear

everything from t-shirts, to messenger bags and socks emblazoned with

the famous photo of Che Guevaraís face on it without having a clue who

he was and what he did. What do you think those young people are going

to take away from seeing your film?

SS: Well, I donít know. Iím hoping that theyíd be motivated to see it for the same reason that I said yes eight years ago, which is, ĎWell, Iíve seen that image my whole life and Iíve no idea who that is.í I looked at it as an opportunity to educate myself, thatís one of the fun things about this job. What I was thinking was, I wanna understand why this is always in here. One of my producers ran into the son of a friend of his whoís eighteen years old and the son said, ďWhat are you working on?Ē And he said, ďWeíre doing this film on Che Guevara.Ē He goes, ďWhoís that guy?Ē ďYou know, the guy in the beret with the moustache.Ē

LMD: The orange shirt.

SS: Yeah! He goes, ďOh, I thought that was the guitarist from Rage Against the Machine.Ē Literally, this eighteen-year-old had never heard of him. Heíd seen the thing and he just thought it was a shirt from a concert.

~ The Lady Miz Diva

December, 1st, 2008

© 2006-2022 The Diva Review.com